He did so as the rebels entered and seized Damascus, seemingly with little fightback from Assad’s government forces. Their lightning advance only began Nov. 27, quickly overrunning the cities of Aleppo, Hama and then the capital itself.

The rebels appear to have capitalized on Syria’s backers being distracted elsewhere: Russia in Ukraine, and Iran and its Lebanese proxy Hezbollah fighting Israel. Nevertheless, many experts did not see this coming. And Moscow was no different.

“What happened surprised the whole world and we are no exception here,” Kremlin spokesman Dimitry Peskov said Monday.

Syria dominated international consciousness for almost a decade, its civil war erupting after Assad crushed peaceful protests during the region-wide 2011 Arab Spring.

It soon became a head-spinning, complex conflict, with Iran, Russia and Hezbollah lining up behind Assad and the U.S., Turkey and others supporting different rebel groups, which in turn fought not just each other but also the Islamic State terror group as it captured and then surrendered large swathes of Syria and Iraq.

But until last month the conflict had been largely at a stalemate, after Assad’s forces regained control of much of the country.

Many Syrians are celebrating and searching

As the rebels swept through Damascus, celebratory gunfire reverberated around the streets as people swaddled themselves in the flag of the Syrian opposition and toppled statues of the fled former ruler.

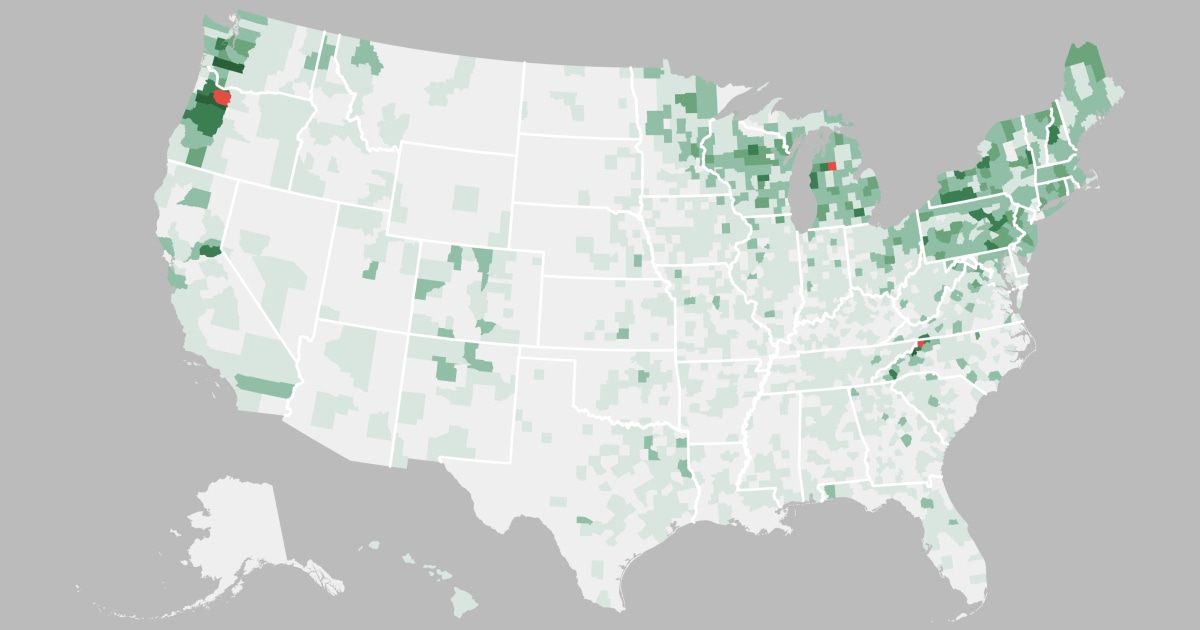

The war saw more than 13 million people flee their homes, according to the U.N.’s refugee agency, UNHCR. Some 7 million of these were displaced within the country, and 6 million abroad — scattered throughout Turkey, other parts of the Middle East and beyond. The conflict in Syria partly contributed to a wave of mass migration into Europe, met by a right-wing backlash across the continent that is still reverberating today.

Much of this diaspora has also responded to Assad’s downfall with astonished glee, some rushing to return home.

Thousands of people rallied across European cities such as London and Berlin, capital of the continent’s biggest Syrian population, Germany, where more than 1 million of them live. It wasn’t just the fighting they were escaping.

The brutality of the Assad regime was illustrated in stark detail Sunday as Syrians began freeing people from the regime’s network of political prisons — essentially dungeons — where rights groups say it disappeared, tortured and executed its own people.

One of these liberated gulags was Saydnaya military prison outside Damascus — known as the “human slaughterhouse” — where Amnesty International says people were executed every week, an estimated 13,000 in total. On Monday it was being searched after survivors reported the possible presence of secret underground jail cells, with families across the country looking for loved ones long held as political prisoners.

What next for the rebels?

That brutality has been replaced with uncertainty.

The rebels are led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a group that grew from an Al Qaeda affiliate. Its leader, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, had been previously involved with militants battling American forces in Iraq following their 2003 invasion. And the State Department has a $10 million bounty for information about him.

In recent years he has sought to project a more moderate image, however, cutting ties with al-Qaeda, renouncing international extremism and instead focusing on creating an Islamic republic in Syria. He says he supports religious tolerance and internal debate.

This was echoed in its order via Syria’s state newspaper Monday that there should be no controls on women’s clothing.

Even so, myriad complexities and problems remain.