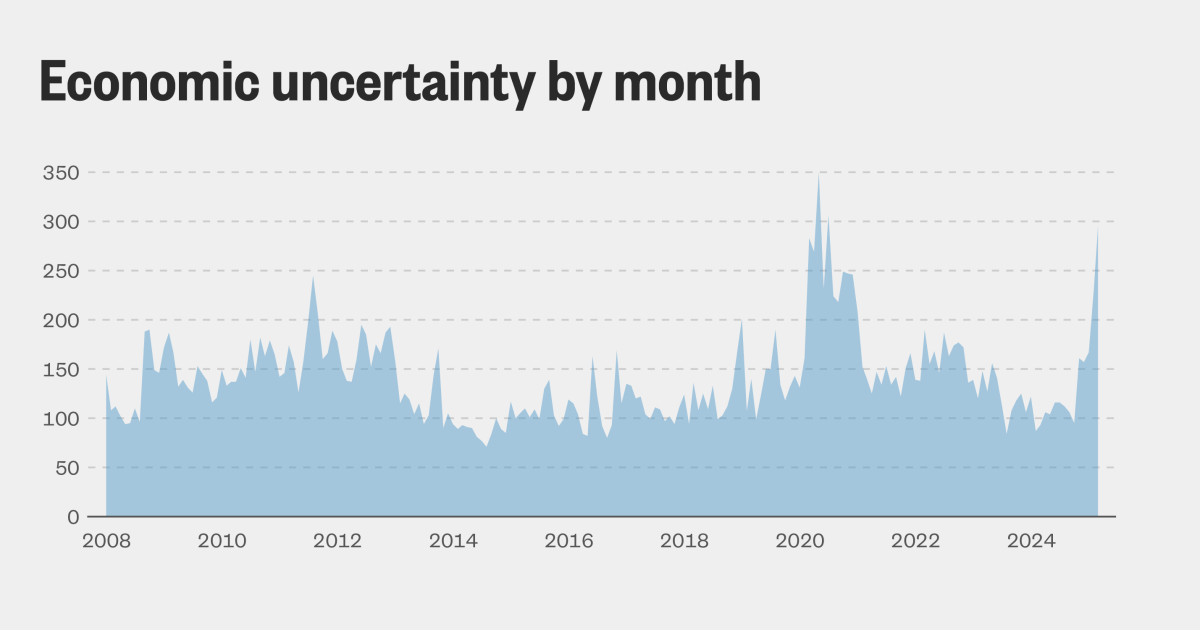

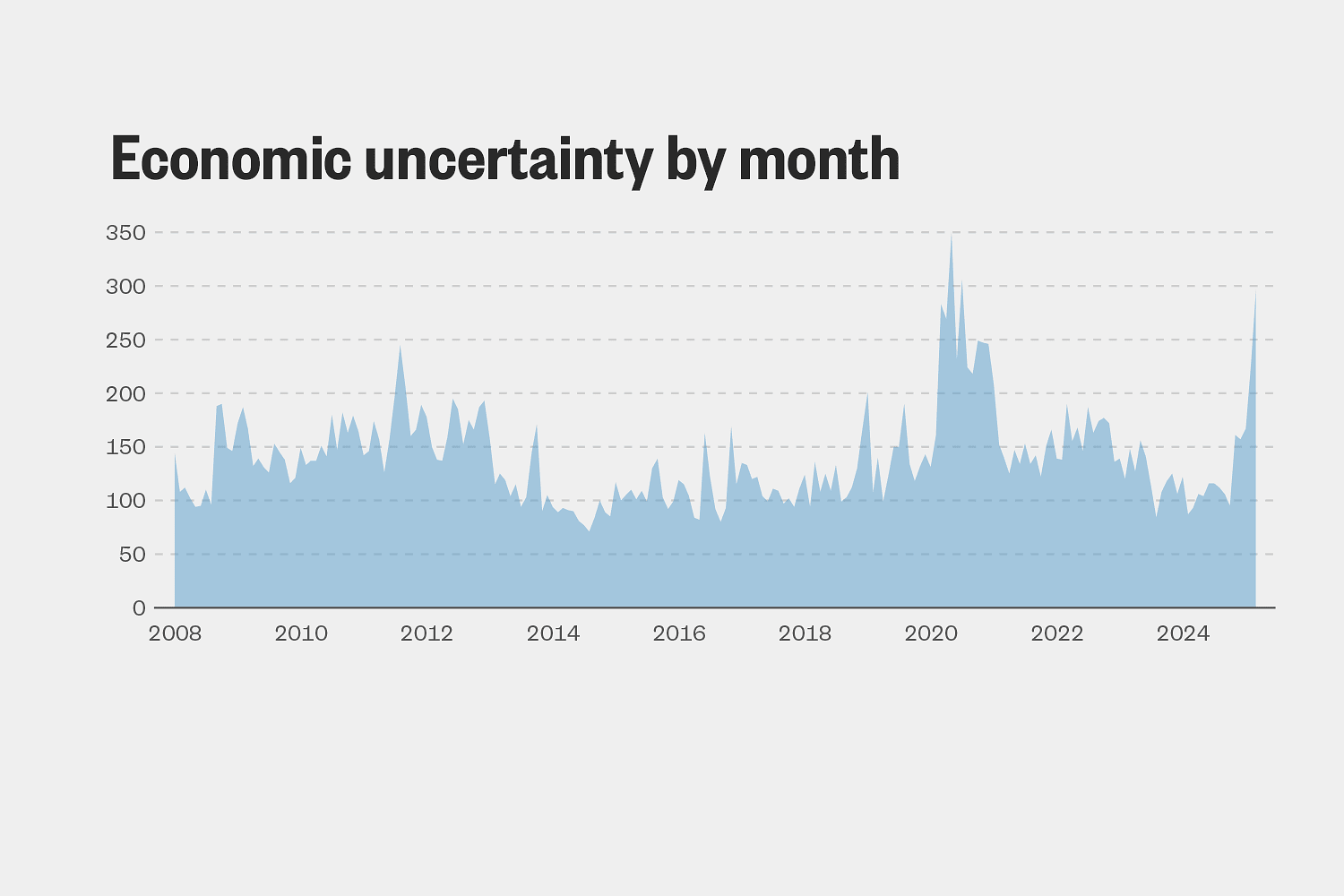

Kevin L. Kliesen, an economist at the St. Louis Federal Reserve, noted that the change in uncertainty from last spring to this spring is the sharpest such increase in almost 40 years.

“It’s a historically unprecedented increase,” Kliesen said.

The instability makes it harder for companies and consumers alike to make decisions, and it can be a scene-setter for recessions. “Firms will delay investment in response to higher uncertainty,” Kliesen said. “Consumers facing higher uncertainty about job prospects, they might cut back on spending.”

Menzie Chinn, a professor of public affairs and economics at the University of Wisconsin, said, “People are maximally confused.”

To show how uncertainty plays out, Chinn gave an example of potential homebuyers: Lowering interest rates might entice them, but worries about a big drop in home prices over the next year — the kind that might arise from a recession — might scare them away.

“It’s better news, but washed out by this bad uncertainty,” Chinn said.

The uncertainty extends into the bond market: Government bonds are being sold more than they’re being bought — even as stocks sour, flouting historical trends.

Traditionally seen as a safe harbor, bonds tend to be purchased by investors when markets are on edge. That’s not the case today, with 10-year Treasury yields surging above 4.5%.