Doctors and researchers across academic institutions fear that the National Institutes of Health’s decision to cut indirect research funding could stall medical progress and negatively affect patient care.

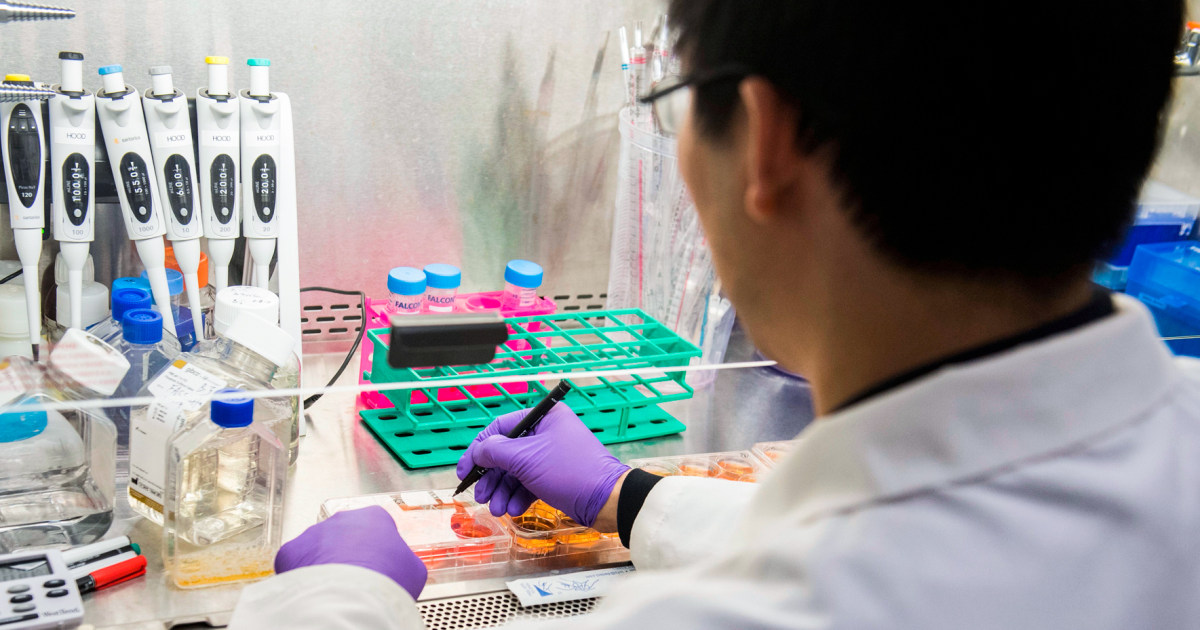

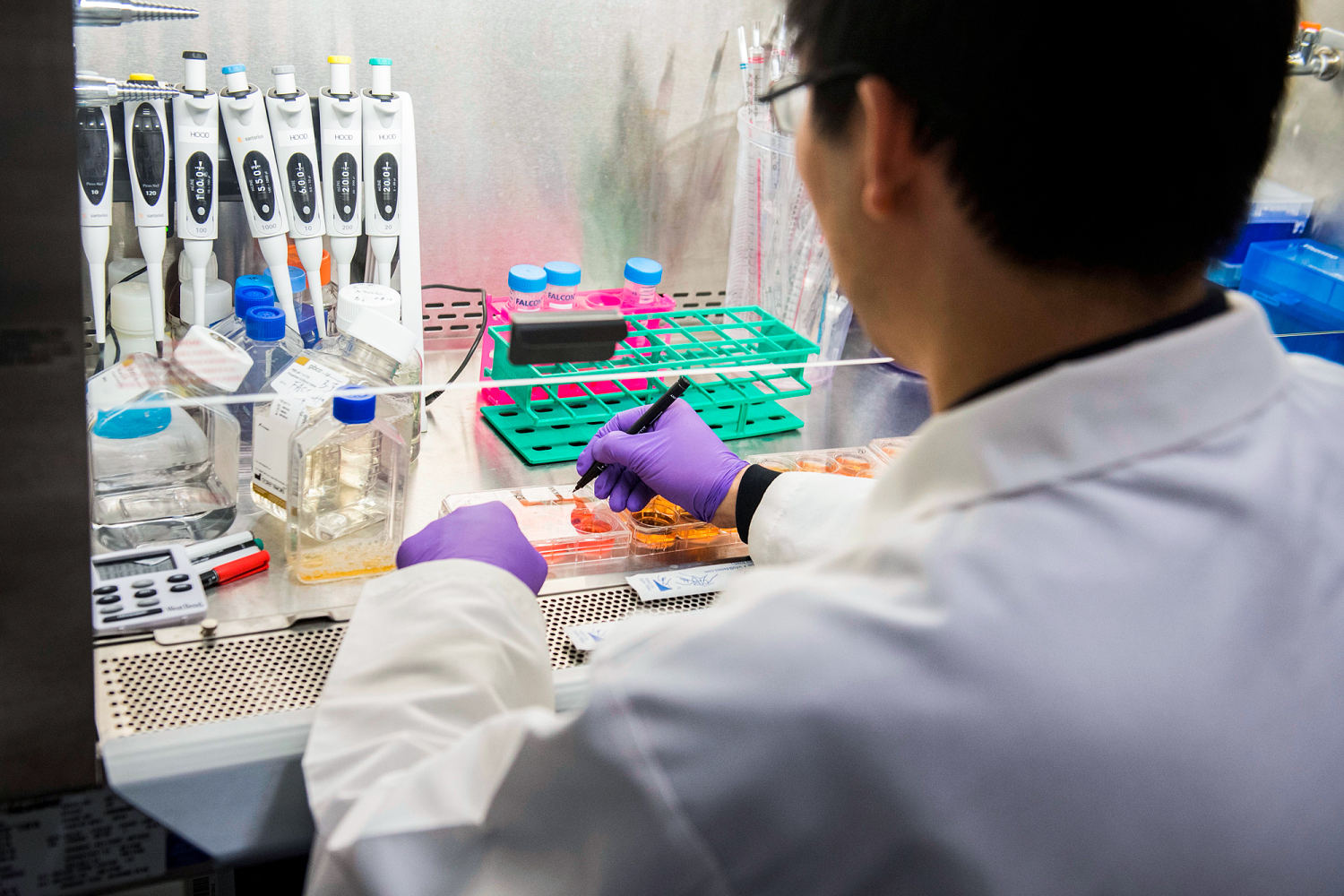

Indirect funding covers things like equipment, buildings, maintenance, utilities and support staff.

The funds aren’t used to directly support patient care but are crucial for basic operations at research institutions, said Dr. Theodore Iwashyna, a pulmonologist and critical care physician at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, paying for computers, whiteboards, microscopes, electricity, and janitors and staff who keep labs clean and organized.

The money supports “the research infrastructure,” said Iwashyna, who relies on NIH funding for research on chronic illnesses, including pneumonia, among the leading causes of hospitalizations in the U.S.

Iwashyna’s father had pancreatic cancer, and the care plan developed for him existed only because of research funded through organizations like the NIH.

“Everybody who comes to a place like Johns Hopkins, who comes to a place like Ohio State University to get a second opinion, the ability to do that depends on the research they’re doing,” he said.

Under the NIH’s new policy, which temporarily went into effect Monday, payments for indirect costs will be capped at 15%, down from around 27% or more — a reduction, Iwashyna said, that will cost jobs and prevent experts from researching important medical issues including cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

On Monday, however, a federal judge temporarily halted the new policy following a lawsuit from 22 state attorneys general.

The lawsuit claimed that the change will be “immediate and devastating” and will “result in layoffs, suspension of clinical trials, disruption of ongoing research programs, and laboratory closures.”

Dr. Robert Golden, the dean of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, said indirect costs aren’t just administrative tasks, or “waste,” but the physical structures and equipment needed to do “top tier” research.

“I’ve been at several public institutions, including the NIH early in my career, and never saw waste to a striking degree,” he said.

The NIH’s change, Golden said, “will have a profound significant impact on everything,” including utility charges, building out the laboratories where scientific experiments are done and finding cures for patients.

What is a direct cost in research?

“Direct costs” cover things like clinical research, patient care and scientists’ salaries.

“Direct cost is the groceries,” Golden said. “Indirect costs are the money you need to have a refrigerator and to pay your electric bill so that the milk and eggs don’t go bad.”

The amount given to institutions varies and is based on a percentage of the direct research costs in a grant. Big-name institutions, like Hopkins, often get bigger rates.

Matthew Cook, the president and CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association, which represents more than 200 children’s hospitals, urged the Trump administration to rescind its guidance.

“Reducing the indirect cost rate will threaten the ability of children’s hospitals to provide future groundbreaking cures for children,” Cook said in a statement.

The NIH estimates that its cost-cutting move could save the government and taxpayers more than $4 billion a year.

Elon Musk, the head of the Trump-appointed group aimed at reducing federal spending, praised the NIH announcement on his social media platform X, calling the previous policy “a ripoff!” Musk quoted a post from the NIH that said last year, $9 billion of the $35 billion that the agency granted for research was used for administrative overhead, also known as indirect costs.

Other medical and academic groups pushed back on the NIH’s new policy.

The president of Harvard University, Dr. Alan Garber, who is also a physician, said in an email Monday that the discovery of new treatments will slow and the opportunity to train the next generation of scientific leaders will shrink.

Indirect costs “are substantial, and they are unavoidable, not least because it can be very expensive to build, maintain, and equip space to conduct research at the frontiers of knowledge,” he said.

In a statement, Dr. Tina Tan, the president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, said the cuts will “eliminate the promise of lifesaving medical treatments.”

It will “leave our nation less safe and more vulnerable to disease outbreaks and bioterror attacks, and hurt our economy,” Tan said.