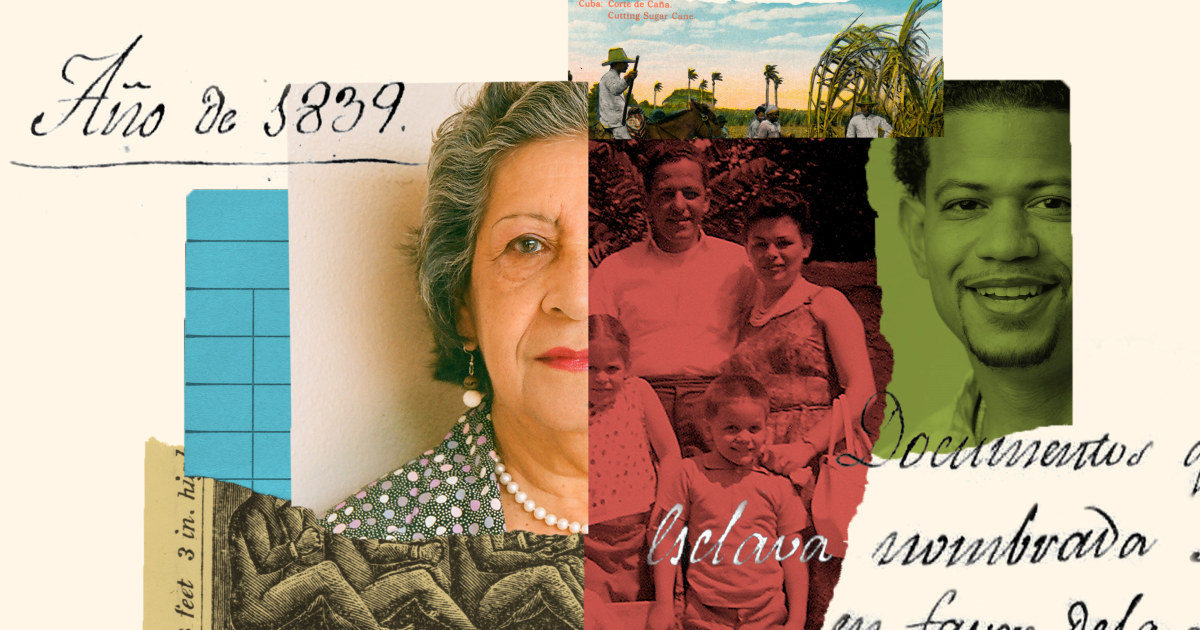

Through SlaveSocieties.org, this reporter confronted his own family’s slave-owning past: Notary records from Cartagena, Colombia — once the largest slave port in South America — revealed an 1831 will of a previously unknown fourth-great-grandmother who left her daughter three enslaved youths as well as 100 pesos to purchase yet another slave. This reporter never thought that their humble Colombian immigrant grandmother, who sewed garments in New York sweatshops, could have been three and four generations removed from slave owners.

Exploring his own family tree, Texas-based genealogist Moises Garza uncovered both Afro Mexican ancestors and slave-owning forebears, reflecting the estimated 200,000 enslaved Africans brought to colonial Mexico. Garza first became interested in genealogy when he and his father were migrant workers in Texas, listening to his father’s family stories during long hours picking carrots. Over a quarter century later, Garza has compiled an online database with 1.1 million names from northeastern Mexico and Texas, and feels no need to distance himself from forebears who were conquistadors or slavers.

“I’m not going to say I’m embarrassed or going to apologize for what they did, because I have ancestors on both sides,” Garza said. “Some were the conqueror, some were the conquered. History is history and we learn from it. Or we get mad about it, but what’s the use of that?”

Gates said one is not restricted “to the good or bad things that your ancestors did — you want to go back to the original sin, look at the complicity between African merchants and elites and European merchants and elites over the course of the slave trade.”

“It’s a nasty and dishonest business to attempt to hold a person responsible for the stuff their ancestors did,” Gates said.

And yet uncovering the history of slavery is important, especially when so many Latin American families hid or intentionally forgot their African and Indigenous roots.

“Enslavement [and] genocide were designed to cut the ties that bind,” said Teresa Vega, an African American and Puerto Rican genealogist and public educator based in New York. “So you have to follow these DNA trails, figure out and flesh out your [family] trees and look for all possibilities.”

Vega’s parents separated when she was little, and it took a DNA test for Vega to connect with her paternal Puerto Rican family.

“I had been to Puerto Rico before, but I reconnected with my Taíno and Afro Indigenous side,” Vega said. “I feel like I’m 100% who I am.”

Giselle Rivera-Flores, a communications director in Worcester, Massachusetts, didn’t need a DNA test to know she was Afro Latina — her Puerto Rican family’s “Black skin and coarse hair” made that obvious. But finding out that 40% of her DNA matches Africans in countries like Cameroon, Congo, Nigeria, Senegal, Mali and Benin gave her “a sense of identity — one that no one can take away from me or debate about.”

While Rivera-Flores still has trouble convincing her mother and older relatives to embrace their Afro Latino heritage, she wants her three young children to know the insights she’s gained by knowing where she comes from.

“Staying true to who you are opens up a new perspective on how you view the world,” Rivera-Flores said. “It connects you with a lot of empathy for people.”

‘Here they are’

Following the loss of her Puerto Rican grandfather, filmmaker Alexis Garcia made her 2022 short film “Daughter of the Sea.” The film, which stars rapper Princess Nokia, draws inspiration from the Yoruba faith, an African religion practiced in Latin America.

Garcia first learned about the Yoruba faith at her grandmother’s botánica (religious goods store) in the Bronx, where her devout Catholic grandmother, Jerusalén Morales, called on Yoruba orishas (spirits) during spiritual readings and kept statues of orishas alongside Catholic saints. But it took years for Garcia to appreciate how the orishas directly connect her with her African roots.

“This is part of our inheritance. We didn’t have a material inheritance, but we have this spiritual inheritance,” Garcia said.

When Garcia tested her DNA, she found it “thrilling and emotional” to learn her direct maternal DNA — inherited from the grandmother who ran the botánica — comes from the Igbo people of Nigeria.

“To tell my mother and my grandmother the proof of who we are and where we came from … I feel like there was a spark from me to seven generations in the past,” Garcia said.

Garcia and her cousin Selina Morales have started a film production company, and they’re working on a feature film and a documentary on traditional healers in Puerto Rico. When they named the company, their grandmother once again provided inspiration: Botánica Pictures.

“Selina was told by our grandma that she was going to own a botánica. At that time she was like, ‘There’s no way I’m going to own a store selling candles,’” Garcia said. “When we landed on the name, I understood the prophecy from our grandmother.”