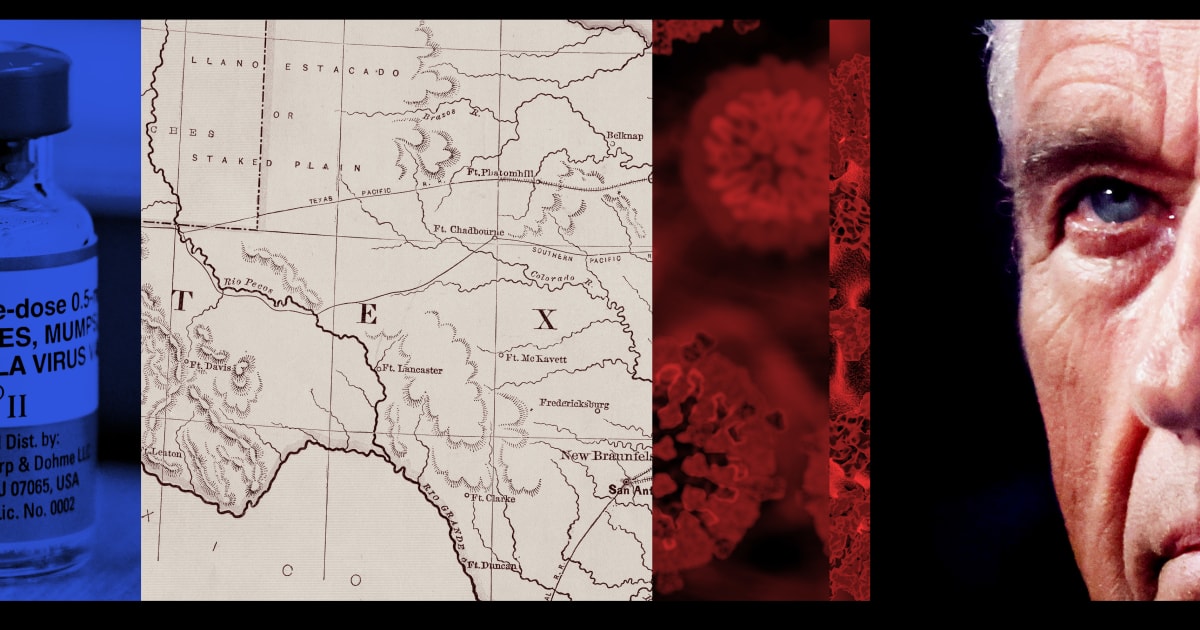

A child in the United States has died from measles.

Just two weeks after his confirmation as Health and Human Services secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. faces the public health crisis that experts have long warned would come.

Little is known about the child, besides that they were school-age, unvaccinated and lived in an area of West Texas with a large Mennonite community, where vaccine refusal is among the highest in the country.

In another administration, the death of this child, and the growing outbreak that has sickened more than 150 across Texas and New Mexico and hospitalized 20, would likely have been met with urgent calls from the president and health secretary for parents in Texas and beyond to vaccinate their children. The measles, mumps and rubella vaccine is safe, well studied and the only effective method of preventing an illness that can cause a high fever, pneumonia and, in rare cases, brain swelling that is disabling or fatal.

But this is public health in the Kennedy era, where the secretary’s life’s work has been dismantling trust in the very vaccines that could have prevented this outbreak, and where the public official now in charge of the agencies that regulate and advise on vaccines wrote in a 2021 book that measles outbreaks had been “fabricated to create fear that in turn forces government officials to ‘do something.’”

And so, at a Cabinet meeting Wednesday, Kennedy’s response to the child’s death offered something else entirely: an unconcerned and casual reply.

“We are following the measles epidemic every day,” Kennedy said, adding that “incidentally, there have been four measles outbreaks this year. In this country last year there were 16. So it’s not unusual. We have measles outbreaks every year.”

Kennedy then said that the hospitalized children were there “mainly for quarantine,” an assertion swiftly dismissed by the chief medical officer at the Lubbock children’s hospital where they are being treated, who described the admitted children as having difficulty breathing.

The next day, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posted a statement on its website offering condolences for the child who died and outlining ways it was supporting Texas and New Mexico health agencies as the states lead the on-the-ground response. The statement included a line on vaccines as “the best defense against measles infection” but did not urge the public to get vaccinated. A day after that, Kennedy posted a similar note to his official account on X, concluding, “Ending the measles outbreak is a top priority for me and my extraordinary team at HHS.”

The White House and HHS did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Despite Kennedy’s claims, the death of a child from measles — while common in countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia — is unusual here. And Kennedy is an unusual HHS secretary.

The U.S. officially eliminated the measles in 2000, and the last time a child died was over two decades ago: a 13-year-old boy with a chronic immune disorder who had recently undergone a bone marrow transplant. Around the same time, Kennedy, an environmental lawyer then known for his public battle with heroin addiction, was diving down the anti-vaccine rabbit hole and quickly becoming the movement’s de facto leader and its most vocal purveyor of misinformation.

Dr. Vincent Iannelli, a pediatrician in Rockwall, Texas, a five-hour drive from the current outbreak, has been debunking Kennedy’s claims since 2016 on his website Vaxopedia. Early on, Kennedy focused on thimerosal, a preservative, but after it was removed from most childhood vaccines in 2001, Iannelli said Kennedy shifted to other ingredients, known and unknown, falsely blaming them for myriad childhood illnesses.

Iannelli said Kennedy’s books were too abundantly wrong to be fact-checked in full, so he settled for blogging on the “first five lies” he found in each, noting he never got past the third page.

“It was all lies and misinformation,” Iannelli said.

Over the past 20 years, Kennedy, as head of the group he led, Children’s Health Defense, has been found in the places where measles threatened children most, often cinematically amplifying his anti-vaccine rhetoric through a bullhorn to the most vulnerable: to Minnesota’s Somali refugee community in the midst of a 2017 outbreak, to New York’s capital in 2019 where he urged lawmakers to weaken school vaccine mandates amid another outbreak, and that same year to Samoa, where he lobbied the prime minister to reconsider the mass vaccination campaign that ultimately stopped a measles outbreak, but not before it sickened thousands and killed 83, mostly small children.

During his decades of activism, Kennedy has made clear who he believes to be the villains in his vaccine conspiracy theories. In keynote addresses at annual conferences for an organization built around the false idea that vaccines cause autism, he attacked the CDC as a “cesspool of corruption,” filled with profiteers who knowingly harm children, and likened scientists to Nazi guards. According to Kennedy, drugmakers, the government, the media and the entire scientific community are covering up the threat vaccines pose to children.

But it wasn’t until Covid that Kennedy found a mainstream audience for his anti-vaccine ideas. In 2022, Children’s Health Defense, after quadrupling its annual revenue over the course of the pandemic, heralded the “silver lining” of a virus that had killed over 1 million Americans: Childhood vaccine rates were also plummeting. Kennedy then took his ideas on the road in a failed presidential run that appealed to a coalition of anti-vaccine activists, wellness influencers and disaffected libertarians — ultimately drawing the attention and partnership of Donald Trump, who embraced his former rival as a figurehead and rallying force for what Kennedy branded MAHA (Make America Healthy Again), a coalition skeptical of government and public health institutions.

“MAHA is a position that is anti-science and anti-public health,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of public health law at Georgetown University. “The through line of all of it is a war against science and career scientists that have kept America healthy and safe for more than a half century.”

Now, Kennedy sits atop the very system he spent decades attacking, responsible for the nation’s health policy and already chipping away at the institutions he’s been appointed to lead.

His first two weeks have been busy. His short tenure has been marked by mass firings of CDC personnel, many tasked with disease detection and outbreak response; the cancellation of a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee meeting that would have selected the virus strains for next season’s flu vaccine (he has said he suspects a disorder that strains his vocal cords was caused by the flu vaccine); the indefinite postponement of a CDC advisory committee that votes on recommendations for childhood vaccine schedules; the cancellation of pro-vaccination advertising campaigns, reportedly shifting the focus from the danger of diseases like flu to the potential risks of vaccines; and a proposal that HHS end notice and comment procedures for rules related to “public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts,” a policy that seems to run counter to his promise for “radical transparency” at the agency.

His supporters in the anti-vaccine movement couldn’t be prouder.

Del Bigtree, head of the anti-vaccine group the Informed Consent Action Network, leaders at Children’s Health Defense and dozens of other prominent anti-vaccine influencers have rallied to Kennedy’s defense since news of the measles death in Texas. They have argued a single death, while devastating, does not constitute a public health crisis and that public attention would be better spent on other threats.

Bigtree devoted a segment to the Texas outbreak on his internet TV show “The HighWire” on Thursday. In an interview with a Long Island pediatrician well known for encouraging parents not to vaccinate, Bigtree ran through the usual script — downplaying the outbreak, questioning whether measles was truly the cause of death for the Texas child, and pushing unproven treatments like vitamin A over vaccines. He ended with a satisfied nod to the administration. “Our guy is now head of HHS,” Bigtree said.

For public health experts, though, Kennedy’s earliest actions are a warning.

“I think this is the beginning,” said Dr. Paul Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who serves on the FDA vaccine advisory committee whose meeting was canceled this week.

“When I saw a picture of Kennedy sitting in front of the big emblem that said Department of Health and Human Services, that to me was the beginning of a horror movie,” said Offit, the co-inventor of a rotavirus vaccine. “And I cannot believe it will last. I cannot believe that someone who has an anti-public health stance like he has, can last. Because measles is coming to get him.”

Whether Kennedy’s reign could be upended by his response to a measles epidemic remains to be seen. But if this is just the beginning, the question may be: Now that an anti-vaccine activist wields influence over the nation’s food, medicine and health infrastructure, where will he aim next?