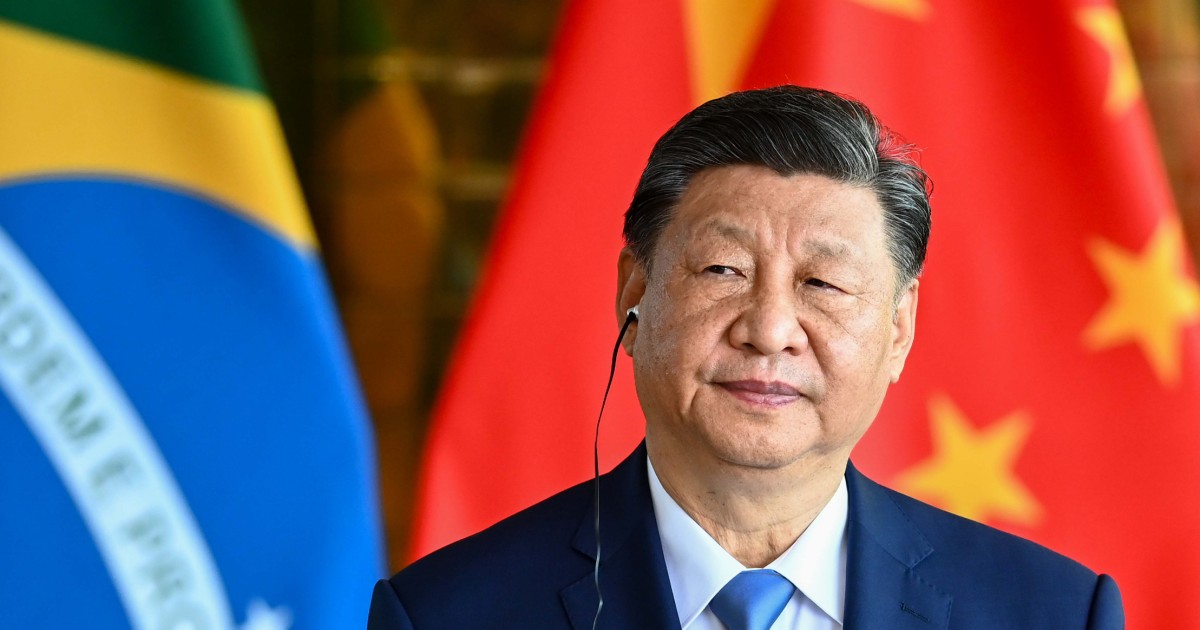

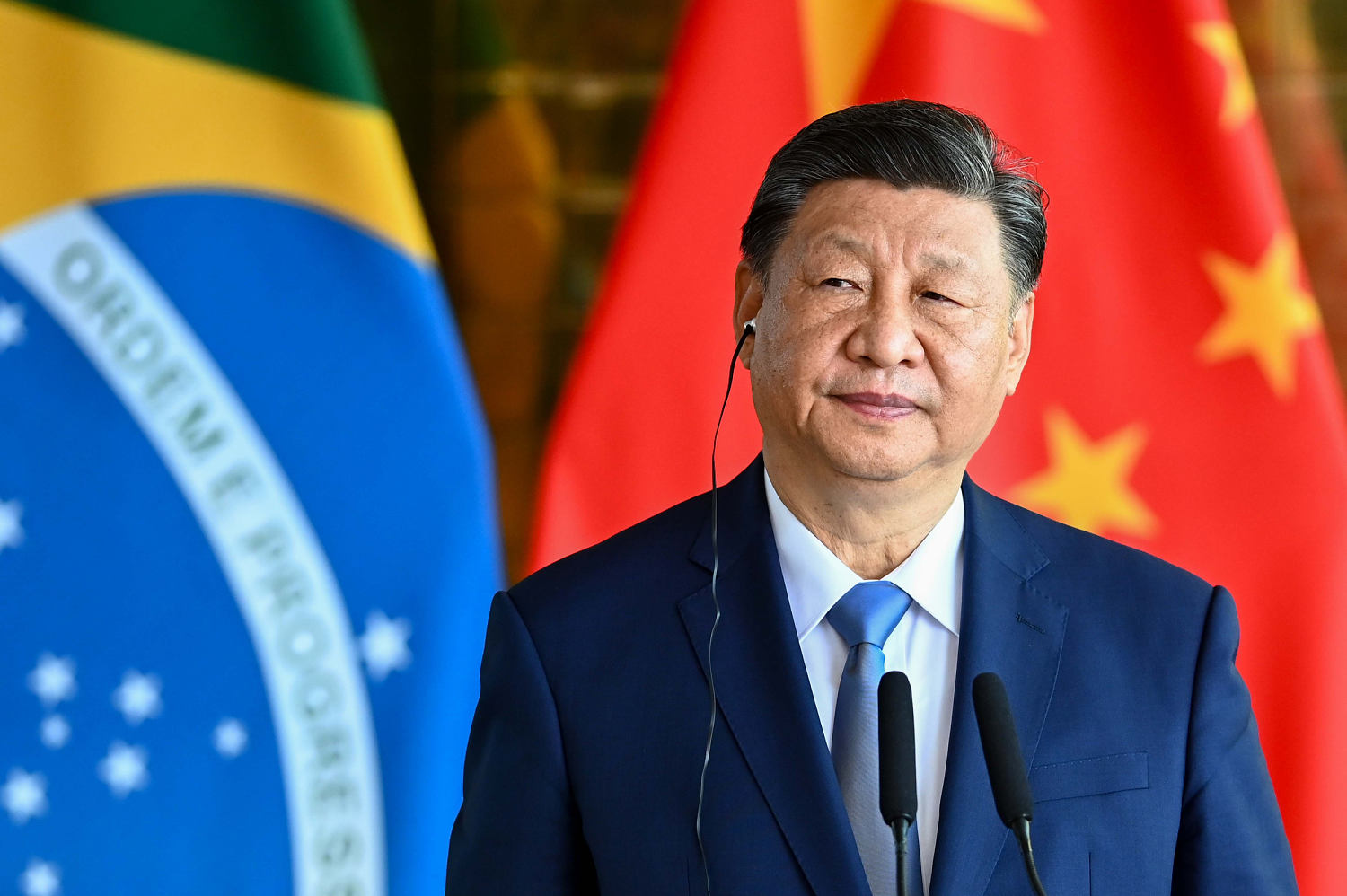

Corruption is the biggest threat to China’s Communist Party, President Xi Jinping said on Monday, in a clear warning that the ruling party is resolved to tackle a long-running problem that is now entrenched in many strata of Chinese society.

China was rocked last year by corruption probes into high-profile individuals ranging from a deputy central bank governor to a former chairman of its biggest oil and gas company, adding to unease in an economy struggling to secure a firm footing and a society grappling with a fading sense of wealth.

The list also included a top Chinese admiral, Miao Hua, whose fall from grace comes at a time when Beijing is trying to modernize its armed forces and boost its battle readiness.

Not only is corruption still pervading China, it is actually on the rise, Xi said at the start of a three-day congress of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the country’s top anti-graft watchdog.

“Corruption is the biggest threat to our party,” he warned.

To underline the scale of the problem, the CCDI said in recent days that a record 58 “tigers”, or senior officials, were probed last year.

Of those investigated, 47 were at the vice-ministerial level or above, including Tang Renjian, former minister of agriculture and rural affairs, and Gou Zhongwen, former head of the General Administration of Sport.

Even former high-ranking officials were not spared, such as Wang Yilin, who stepped down as chairman of state-owned China National Petroleum Corp in 2020 on reaching retirement age.

The crackdown will continue, said Andrew Wedeman, a professor at Georgia State University.

“I don’t see how Xi could afford to back off at this point,” Wedeman said. “A dozen years after he set out to cleanse the senior ranks, Xi is still finding widespread corruption at the top of the party-state and the PLA.”

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has also been swept by a wave of purges since 2023. Li Shangfu was removed as defense minister after seven months and his predecessor Wei Fenghe was expelled from the party for “serious violations of discipline”, a euphemism for corruption.

Wedeman said it appeared that the pool that Xi is drawing on as replacements also included corrupt officials.

“If Xi is promoting corrupt officials, this suggests the party’s internal vetting apparatus is not functioning effectively or, more seriously, is itself corrupted.”

China admits its anti-corruption efforts face new challenges, with traditional forms of corruption such as accepting cash becoming more insidious.

“A businessman might offer me money directly, and I’d refuse,” said Fan Yifei, a former deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve.

“But if he gives it in the form of stocks or other assets, not directly to me but to my family, that’s a whole different matter,” state media quoted Fan as saying.

Even the lowly “flies” and “ants” in China’s vast bureaucracy will not be spared, a program aired on Sunday by the national television broadcaster showed.

The first of four episodes of “Fighting Corruption for the People” that ran ahead of the CCDI meeting focused on grassroots corruption, including a case of how a primary school director profited from kickbacks from on-campus meals and another on how a rural official took bribes from farm project contractors.

“Compared to the ‘tigers’ far away, the public feels more strongly about the corruption around them,” said Sun Laibin, a professor at Peking University’s School of Marxism.

The anti-corruption fight must reach the “hearts” of the masses, he said on the program, so that they can “deeply feel” the care of the party.