The overhaul of South Carolina’s death chamber was completed three years ago. Now, a team of sharpshooters is practicing its aim for what is poised to be the first firing squad execution in the state’s history on Friday.

Death by firing squad remains an extremely uncommon form of capital punishment in the United States, with only three carried out since the death penalty was ruled constitutional in 1976. All three occurred in Utah — the last in 2010, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center.

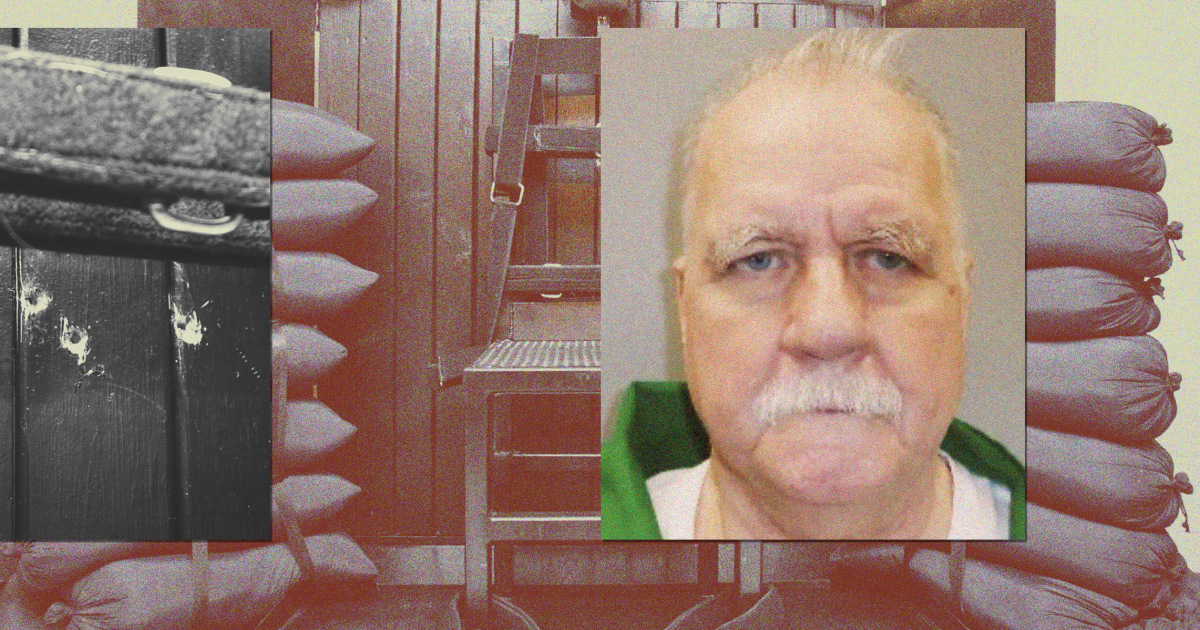

Brad Sigmon, the condemned South Carolina prisoner, opted for firing squad over the state’s primary method of electrocution or the more widely used practice of lethal injection.

“He’s made the best choice that he can, but the fact that he had to make it at all is horrifying,” said Sigmon’s lawyer, Gerald “Bo” King.

Sigmon, 67, who was convicted in 2002 in the beating deaths of his ex-girlfriend’s parents, declined lethal injection, King said, because of concerns over its use in the last three executions in South Carolina.

In a filing last week asking the South Carolina Supreme Court to halt Sigmon’s execution, his legal team noted the state’s autopsy report for Marion Bowman Jr., who was put to death by lethal injection last month, indicates he was given “10 grams of pentobarbital” and “died with his lungs massively swollen with blood and fluid,” akin to “drowning.”

That amount of pentobarbital is double what corrections officials had attested to needing under the state’s lethal injection protocol, according to the filing.

King argued that the state must disclose more information about the protocol and the quality of its pentobarbital on hand in order for Sigmon to have made a fair choice.

State prosecutors said in a response Friday to Sigmon’s filing that because he chose death by firing squad, he has “waived any argument about lethal injection.” They also contend the second dose of pentobarbital was administered as outlined under the state’s protocol and nothing was unusual with how the other inmates died.

With Sigmon’s execution drawing closer, barring a last-minute reprieve, the return of a firing squad execution is also raising questions about whether it is ushering a new — yet old — chapter in America’s use of the death penalty.

During the Civil War, firing squads were common for executing soldiers for desertion; in some cases, they would be blindfolded and tied to stakes before being shot. A century ago, Nevada executed a prisoner using an automated machine that fired the bullets so that no person had to.

In the modern era of capital punishment, only a handful of states, including Mississippi and Oklahoma, allow for the method, with South Carolina legalizing it in 2021 and Idaho following two years later amid a nationwide shortage of lethal injection drugs.

Corinna Barrett Lain, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, said states are moving to the firing squad because lethal injection has been problematic, with reports of “botched” incidents in recent years.

“States can’t get the drugs. They can’t get qualified medical professionals to do it,” Lain, the author of the upcoming book “Secrets of the Killing State: The Untold Story of Lethal Injection,” said in an email.

“The firing squad is too honest, too explicit about what the death penalty is. People tend to think it’s barbaric and archaic,” Lain said, adding: “In that way, it may start some very important, and long overdue conversations about the death penalty in this country.”

Utah’s use of the firing squad

The last firing squad execution, in 2010, lasted about four minutes, from when the death chamber’s curtain was lifted to when the bullets struck Utah inmate Ronnie Lee Gardner, according to media witnesses.

Gardner, 49, was sentenced to death after fatally shooting an attorney, Michael Burdell, and wounding a bailiff, George Kirk, as he attempted to flee a courthouse in 1985. Gardner was already in custody for the killing of a bartender, Melvyn John Otterstrom, a year earlier.

Prison staff members strapped Gardner to a chair, and after he declined to make a final statement, fit a black hood over his head. A small white target with a bull’s-eye pattern was fastened to his chest. Five shooters — volunteers described as certified police officers — fired .30-caliber Winchester rifles from behind a wall with a gun port.

The number of shooters helped to ensure one of the bullets was fatal, although one firearm was also fed a blank so that each shooter was uncertain who was directly responsible for the death, officials said.

Media witnesses described Gardner appearing to flinch and move his arm after being shot, leaving them to wonder if he was still alive and would have to be shot again. But a medical examiner declared him dead a short time later, they said.

Jennifer Dobner, who covered the execution for The Associated Press, said it was a “very clinical and precise procedure.” Fifteen years later, she still recalls a “boom, boom” from the rapid gunfire, then “the target on his chest kind of blew up, the fabric kind of blew up,” and the room fell silent. The execution was traumatic for the Gardner family, she said.

“They have their own trauma from losing their brother this way. Not that they condone anything that he did, but it is a very extreme form of punishment,” Dobner said.

Jamie Stewart, Kirk’s granddaughter, witnessed Gardner’s execution with her grandmother. Kirk died a decade after the shooting.

Stewart said she initially thought the execution was going to be more gruesome.

“It’s over really quick,” Stewart said in a text. “It’s not anything like I expected it to be.”

To her, it was “the most humane” way for Gardner to die, she said. “Everyone thinks it’s horrible to die this way, but how many botched firing squad executions have there been?”

Gardner’s death “gave me closure,” she added. “That monster finally paid for his crimes.”

Gardner’s brother Randy Gardner said none of his family witnessed the execution but he has since become an advocate against the death penalty.

The method of his brother’s death has haunted him, he said.

“I’ve gone through years and years of nightmares of me executing my mother in a wheelchair and executing my kids and my kids executing me,” Randy Gardner said. “And, you know, after six, seven, eight years of that, I finally had to get a therapist.”

Randy Gardner later saw his brother’s body and also received graphic autopsy photos showing the extent of the wounds. His socks were soaked red from the blood.

“It’s not going to be pretty in South Carolina,” Randy Gardner said.

What is planned in South Carolina

At the Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, the shooters are volunteers employed by the Department of Corrections. Per officials, the three-person squad will fire rifles, all with live ammunition, from behind a wall about 15 feet from the inmate, who will be seated.

Before the shooting, the inmate is allowed to make a last statement, then a hood is placed over his head and a target pinned over his heart. Bullet-resistant glass separates the chamber from another room where witnesses, including media, will be permitted.

The department provides mental health support to staff members who are taking part in executions, said spokeswoman Chrysti Shain.

D’Michelle DuPre, a forensic consultant in South Carolina and a former medical examiner, said “botched” firing squad executions can be prevented as long as the shooters are properly trained.

“When your heart is struck with a bullet like this, you’re immediately incapacitated,” DuPre said. “There’s relatively no pain. Everything is very quick.”

“If the heart is destroyed, it can’t pump blood to your brain, and the brain is what keeps you conscious,” she said. Muscles may still contract, she added, but “it’s not a sign of life.”

King said Sigmon has spent the past two decades in prison repenting, reading the Bible and praying.

“He’s very devout, and that’s been the organizing principle of his life ever since he went to death row,” King said. “So he’s continued on that course. He is, I would say, fearful about what is looming.”

The execution chamber is located beside death row, and King said inmates “have been treated to the unsettling experience of hearing a lot of gunfire.”

“They don’t know if that’s just folks practicing on the firing range, which is also very close to the row,” he added, “or whether they’re practicing for an execution.”