Indigenous researchers are up against a ticking clock: Of the 4,000 Indigenous languages worldwide, one dies every two weeks with its last speaker. “Within the next five to 10 years, we’ll lose most of the Native American languages in the U.S.,” Michael Running Wolf, founder of Indigenous in AI, an international community of Native, Aboriginal and First Nations engineers, said.

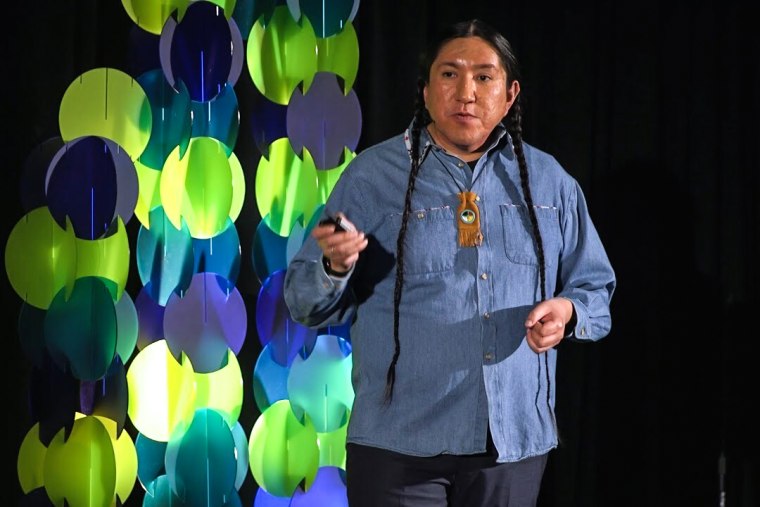

Running Wolf has dedicated his career to preventing this loss. He leads First Languages AI Reality, an initiative of the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute, where researchers are building speech recognition models for over 200 endangered Indigenous languages in North America.

However, first, he must overcome a major roadblock: There aren’t enough Indigenous computer scientist graduates — people who know the language and culture — to tackle these language preservation projects. Running Wolf emphasized that Indigenous scientists know to respect the data itself. “The core data we use isn’t just tweets or social media posts; it’s deeply culturally identifying information from speakers who may have passed away,” he said. “We need to make sure that the community is always retaining their relationship to the data.”

Running Wolf said that in his years of artificial intelligence research, he’s only come across about a dozen Indigenous North American AI scientists. “We only graduate one or two Indigenous Ph.D.s in AI and computer science every year,” he said.

Indigenous people make up less than 0.005% of the tech workforce in the U.S., hold only 0.4% of bachelor’s degrees in computer science every year and have one board member at the top 200 tech companies. In 2022, Native-founded companies only received a mere 0.02% of total venture capital funding.

That’s where the handful of Indigenous engineers who do exist come in: They are leading organizations like First Languages AI Reality, IndigiGenius, Tech Natives and the Wihanble S’a Center for Indigenous AI to train Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian computer science students to preserve Indigenous culture and language.

“Traditionally, AI assumes that data is proprietary, and that can be harmful for Indigenous communities,” Running Wolf said. “We want to demonstrate that we can succeed in our mission of reclaiming Indigenous languages ethically with ethical AI protocols.”

Building the Indigenous-tech pipeline

Kyra Kaya is one of the dozens of beneficiaries of the tech training program Tech Natives, an organization of Indigenous women in tech that offers mentorship and recruitment opportunities on college campuses. Studying computer science at Yale University, Kaya was inspired to build an AI tool that would honor her Native Hawaiian grandmother, with whom she spent summers in Maui. “I realized many Native Hawaiians don’t have access to technology that many people take for granted,” the 20-year-old said.

She fed the tool Hawaiian Pidgin English, a heavily stigmatized English-based creole language used by many Hawaii residents, and trained it to recognize spoken phrases. “I wanted to change the narrative around pidgin as a ‘lesser language,’” she said. “I input phrases that my grandmother, aunties and mother used and got it to identify them.”

Kaya hopes to turn her work into an app accessible to other Hawaii locals. “AI and the tech industry have the power to either uplift or silence marginalized groups like mine,” she said. “That’s why Indigenous people can and should play a large role in it.”

Researchers say getting more Indigenous people into the tech industry begins with piquing their interest at a young age. In South Dakota every summer, IndigiGenius’ Lakota AI Code Camp brings together Native teens for three weeks to design an app that documents the Lakota culture, including sacred plants and everyday Lakota words. Since its launch in 2022, the code camp has trained 33 students to contribute to the app, many of whom have returned as instructors or pursued other computer science projects.

To continue tech education throughout the school year, IndigiGenius has also launched T3PD, training a group of 20 mostly Native high school teachers across the country to develop culturally relevant computer science courses at their schools. Only 67% of Native students have access to a computer science course, lower than any other student demographic, and the organization is partnering with teachers to bring laptops and computer science classes to their students.

“It’s about making AI education culturally relevant for students,” IndigiGenius Executive Director Andrea Delgado-Olson said. “What sets us apart is how we’re utilizing Indigenous knowledge to bridge technology with our traditions.”

Preserving other aspects of Indigenous culture with AI

AI is also helping to fill Indigenous cultural gaps beyond language. As a child, Madeline Gupta seldom visited her Chippewa lands. But as she grew older, the call to return to her ancestral lands grew stronger. “I had this feeling that I belonged on that land, that my ancestors wanted me there,” Gupta said.

She said that after the government tore tribal members away from their land and their families from 1819 to 1969, many were disconnected from their roots. “My tribe has about 50,000 people, but only 2,000 of them live on the reservation,” the 21-year-old Yale student said. “That means thousands of students haven’t seen their own lands.”

In college, Gupta joined the Tech Natives program and proposed an immersive virtual reality experience for Native youth to “visit” their traditional lands in the Great Lakes region. After securing funding from the Aspen Institute and the Yale School of Medicine, Gupta traveled to Mackinac Island this past summer to film and record stories from tribal elders, capturing 3D spatial video on her phone, then recording the audio stories to accompany it. She hopes to create a virtual reality map of the island that users can click into to view videos related to the area.

“I want to reach people who don’t currently feel connected to the land or don’t know our stories,” she said.

In addition to cultural preservation, artists are also using artificial intelligence in their creative practices. Suzanne Kite at Bard College’s Wihanble S’a Center for Indigenous AI describes herself as one of the first American Indian artists to use machine learning in art. “My question is simple: How do we create ethical art with AI by applying Indigenous ontologies?” she said.

Kite dug into the Lakota dream language to process the knowledge that her family received through their dreams from spirits and animals. She spent three months last year recording all of her dreams, then used machine learning to translate the contents into a Lakota women’s geometric language commonly used in beadwork and quiltwork. She also turned her dreams into a graphic score for the American Composers Orchestra. “I try to resist Western personification of AI and instead dig into the hyperlocal, grounded and practical frameworks of knowledge that American Indigenous communities provide,” Kite said.

While many of these Indigenous AI projects are in their early stages, Running Wolf hopes programs like his will be irrelevant in a decade or two. His dream is to revive dying languages and enable new generations of Native speakers to create ethical tech. “I hope this technology will be remembered as an artifact of a troubled time,” he said.