HONG KONG — A key piece of a little-told chapter of World War II history almost ended up in a landfill.

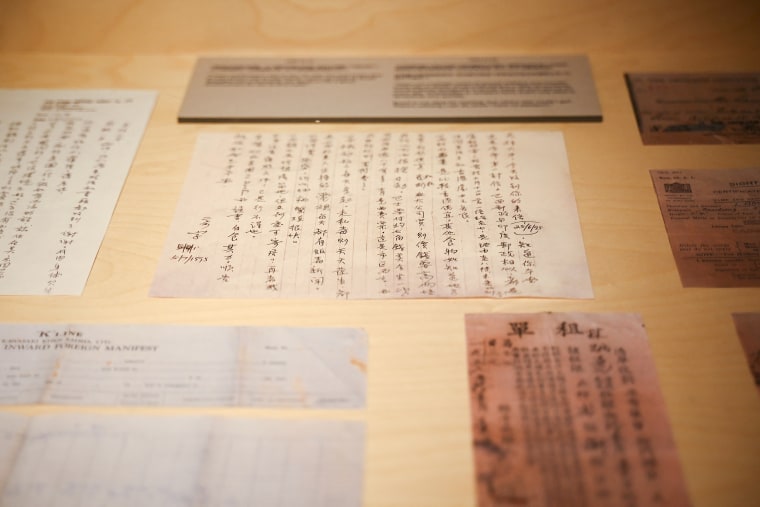

In 2015, a photographer in the Chinese territory of Hong Kong was exploring an apartment building scheduled for demolition when he discovered a number of items from China’s pre-Communist republican era, including a diary from 1944. Photos he shared online quickly drew the attention of amateur historians.

That diary is now believed to be the only known primary source documenting the involvement of Chinese naval officers in the D-Day landings at Normandy. About 80 pages, it challenges previous assumptions that Chinese soldiers fought only in the Pacific theater of World War II.

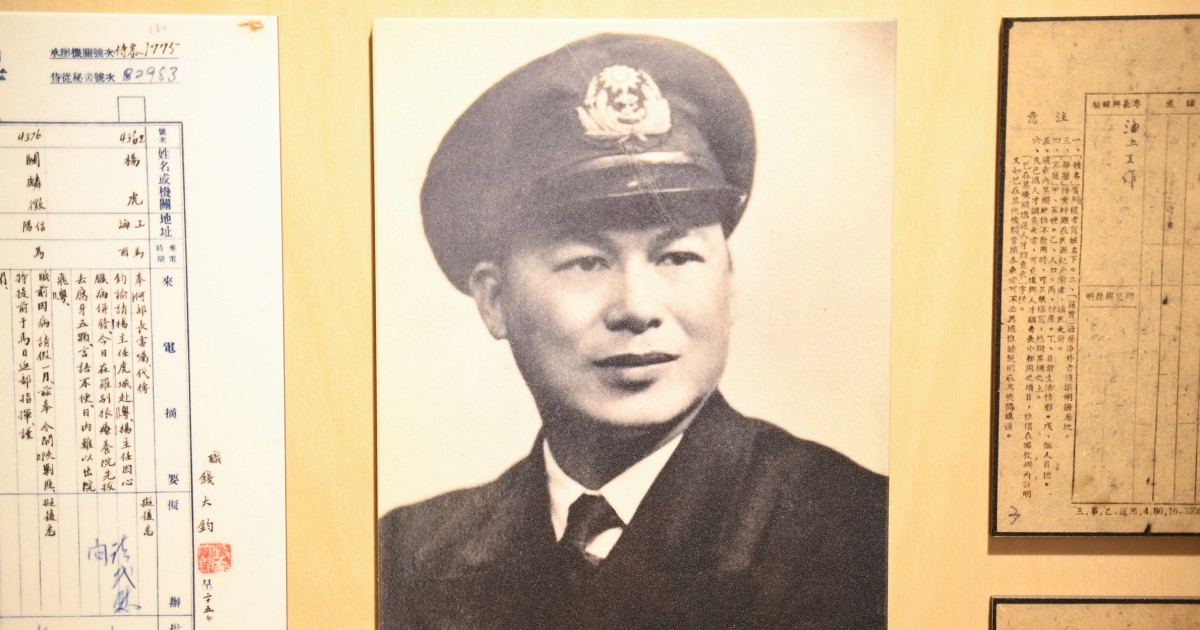

The diary belonged to Lam Ping-yu, an ambitious and patriotic idealist who was born to a well-off Chinese family in Indonesia in 1911 and eagerly joined his home country’s navy. Seeking to enhance his skills as China faced Japanese military aggression, he wrote directly to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek asking to be sent for training overseas, a request that was turned down.

That changed after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, which prompted the United States to enter the war on the Allied side. Lam was among 24 Chinese naval officers sent for training in Britain, describing himself in the diary as “beyond excited,” while several dozen others went to the U.S.

At Britain’s Royal Naval College, Lam and his colleagues studied English and technical skills as well as British naval traditions.

After months of training, they were sent on their very first mission: D-Day.

Crossing the English Channel toward France on the night before the June 6 landings, Lam wrote that the Allied naval vessels were “as numerous as ants, scattered and wriggling all across the sea.”

“In the dead of night, the fleet approached its destination, guided by minesweepers sweeping and dropping dan buoys along the way,” he wrote of the historic military operation, a decisive turning point in the war that led to Germany’s defeat.

Lam and his fellow Chinese naval officers supported the Allied troops on the beaches from one of the British ships off the French coast. But they faced their own danger, narrowly avoiding three German torpedoes because their ship happened to be shifting position at the time, “which was exceptionally fortunate,” Lam wrote. The torpedoes hit a Norwegian destroyer instead.

Lam’s diary shows that “as early as 80 years ago at the pinnacle of war, there was such great, deep friendship” between the East and the West, said John Mak, co-curator of an exhibition about Lam and his fellow Chinese naval officers that opened in Hong Kong last month.

After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Chinese officers were ordered to the Pacific theater. But by the time they arrived a few months later, Japan had surrendered as well.

Lam was reassigned but not before helping to deliver desperately needed supplies to Hong Kong, which had spent years under Japanese occupation.

China, meanwhile, was still embroiled in civil war. When Chiang lost to Mao Zedong’s Communist forces in 1949, he and his Republic of China government fled to the island of Taiwan. The 24 British-trained Chinese naval officers were forced to choose between the two sides, with many of them going on to have distinguished careers in the Chinese or Taiwanese militaries.

Lam was the only one who chose neither. Instead he settled down in Hong Kong, a British colony at the time, where he worked as a merchant seaman until the late 1960s. He then moved to Brazil, leaving the diary behind in his apartment, which he turned over to relatives.

Lam, who married and had two children, ended up moving somewhere in the United States in his 80s, after which Mak and co-curator Angus Hui say the trail goes cold. They say it’s possible that his family, whom they have been unable to find, never knew about his D-Day experience.

The exhibition comes as Hong Kong is reckoning with its changing global role amid an economic slowdown, a controversial homegrown national security law and government crackdowns on dissent after mass pro-democracy protests in 2019.

Lau Suk Yin, a visitor in her 50s who works in publishing, said she found the exhibition inspiring.

“The economy is not good now and many people feel it’s a bit tough,” she said. “However, looking back at history, I think it actually serves as encouragement, reminding people living in Hong Kong, including myself, how to face difficult adversity.”

Hui, the co-curator, said the exhibition showed that “Hong Kong is always relevant in the international arena.”

“Hong Kong is the only place across Greater China where a piece of history like this can be uncovered,” Mak said. “You can always find the shadows of Hong Kong looming in some corners of world history.”